The Pabst name brings to mind visions of beer, Gilded Age mansions, and… skiing? That’s right: From a young age, Fred Pabst, grandson to the famed Captain Frederick Pabst, knew his place wasn’t in the brewery, but gliding through snow. The fact that downhill skiing was basically non-existent in the Midwest at this point did not stop the budding entrepreneur from making his own fun by being towed behind a horse and sleigh, a makeshift form of skiing that would eventually become known as skijoring. At age 18 he began training for Marine aviation, but the end of World War I suddenly cut that plan short, which was fine by Pabst, who said “I hate the government, with their ‘give us 52%,’ but by God, I’m for my country and my flag, right?”

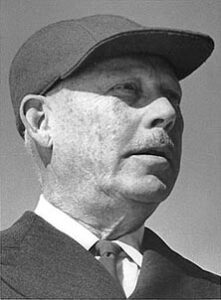

Frederick August Pabst

It’s no surprise Fred was drawn to winter sports considering the history of the family. Growing up in Oconomowoc, playing sports was a huge part of the family culture, and cold weather was no excuse to stop. Sledding, ice skating, snowshoeing and more filled Fred’s childhood winters. Fred Pabst, Jr. (son of Captain Pabst and father to Fred) created the “Ice Boat Comet” to see if sailing in the winter offered a different experience than the summer. It did, as the physics behind ice sailing allow the craft to travel up to five times faster than wind velocity, meaning speeds greater than 70 miles per hour can be reached. Although iceboating had been in existence for centuries before Pabst’s time, the creation of the Ice Boat Comet by his father may have taught young Fred not only how to incorporate curiosity and adventure into his life, but also emphasized the creativity that can be brought to any sport.

With his training derailed, he enrolled in the University of Wisconsin with new plans to expand the sport he loved. After creating the Badger Ski Club, he also founded the Milwaukee Ski Club and effectively showed the U.S. that Pabst was ready to take some real steps in the skiing world.

Fred Pabst, Jr’s Iceboat “Comet”

And that he did. After skiing with the king of Norway and the so-called father of modern skiing, Hannes Schneider, by 1933 Pabst had proved himself more of a ski expert than a beer baron and left the family business to build his own places to ski in his home country. He figured, as he stated in a 1962 Sports Illustrated article, “Why not build my own ski area, right?” he said, “Hell, lots of reasons why not, but nobody knew them at the time.” As this quote foretells, despite his best efforts, there were many problems with Pabst’s grand plan. He took a long trip through America, from Alaska to the Rockies to the West Coast, in search of the perfect place to build a ski arena. Unfortunately, there was too much snow in these places, and the technology to move snow into perfect ski conditions had not been invented yet.

Additionally, there were issues with the remoteness of these locations. They had to be far enough from urban and suburban areas that there was ample room for activities, but close enough to a city that people would actually come. It had to be accessible by train, because in the 1930s remote mountain roads were so dangerous and unkempt they were practically impossible to drive through. Of course, the place had to have snow, and hotels and accommodations for visitors.

Robert and Fred A Pabst on a frozen Oconomowoc Lake

Eventually Pabst settled on St. Sauveur in Canada. From there he looked closer to home, on the East Coast of America, making sure to confirm each location was close enough to New York and Boston to garner visitors from one or both. But Americans, famously, aren’t as friendly as Canadians. “I’d go into a town and try to find cooperation, only usually there was very little,” he said. “I was selling something people didn’t understand. The hard-back Yankees didn’t trust me, a Midwesterner, either.” Indeed, Pabst’s Milwaukee roots harmed his chances of success, but did not stop them entirely. An outdoorsman through and through, Pabst profiled, landscaped and constructed ski slopes throughout New England, and eventually he migrated to Michigan and Midwest.

But Americans weren’t interested. “There just weren’t enough skiers,” Pabst said. “And the hills I’d built were strung out too far apart to supervise properly. I decided to concentrate on one place.” Nestled next to the small town of Peru, Vermont, lay Bromley Mountain. This was the place Pabst decided to focus his efforts, and he wasted no time building a hotel, restaurant, and exclusive lounge. While Bromley was more successful than Pabst’s other endeavors, it failed to actually introduce skiing to the masses due to its high difficulty level: It wasn’t for beginners. Plus, Vermont saw less snow than was needed to keep the skiers going all season, which cut the season short every year. But one day, the aforementioned father of skiing Hannes Schnieder informed Pabst that, “The first area in the East to make its hills smooth so they can be skied on light snowfall will have it.” (It being all the winter sports tourism in the country.)

Bromley Mountain Resort, opened in 1936

Those words would change the course of Pabst’s legacy. When summer came that year, Pabst “planted a catch crop of oats and winter rye, red top and timothy, and a year later the slope lay smooth as a golf green under a scant four inches of snow,” which brought Bromley to the attention of novices as well as experts. He continued to do this to each trail throughout Bromley until every slope was ideal for all kinds of skiing for even longer periods of the year.

Although Sports Illustrated described Pabst as “the only man who ever built, owned and operated 17 different ski areas, with all of them going broke at the same time,” he certainly is also the only man to even attempt to bring a sport so European and seemingly impossible to Americanize to the masses. And he defends his string of failures vehemently – “It’s easy enough to criticize my choice of areas now, but when you’re 15 years ahead of skiing, that’s another story.”

Pabst himself stated that “You never get rich in the ski business,” and while it’s true that he may have not reached the same level or wealth or acclaim as his remarkable grandfather, it would be entirely incorrect to say that Fred Pabst was inconsequential to the country. He devoted his life to sharing skiing with others and was rewarded with a place in the U.S. National Ski Hall of Fame, and despite his myriad of failures at the beginning of his career, Bromley Mountain remains a popular resort with 47 trails, including glades and freestyle terrain park, proving you don’t need to stick to the family business to make history.

By Nora McCaughey