By John Eastberg

In today’s world of digital communications I often wonder if historians of the future will feel the same electric connection that I have when holding or viewing letters from historical figures. The connection of a historic letter is not just its content and what that may tell us about the past, but the tangible link that physical letter had to the person who wrote or signed it. It is that feeling of connection that led many in 19th century America to collect autographs and signatures – I suppose not unlike the selfie taken with a celebrity today.

While the tradition of collecting autographs was strong, especially in the German-American community around the time of the Civil War, signature collection rarely went beyond personal use. However, one Milwaukeean proved an exception when she managed to amass an unparalleled assemblage on behalf of a civic art project to honor Wisconsin soldiers who fought to preserve the Union during the Civil War.

Wisconsin provided exceptional service during the Civil War, especially the 26th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment, which organized in Milwaukee in 1862 and participated in many of the important battles of the Civil War, including the Battle of Gettysburg. Milwaukee was a proud Union city and shortly after the conclusion of the Civil War, there was justifiable interest in erecting a public monument to recognize the extraordinary service and sacrifice of these soldiers to protect the Union.

While the sentiment and desire for building an appropriate statue abounded, the funding was slow to materialize, ultimately taking decades. In spite of broken promises, two major financial panics, and unforeseen delays that plagued the creation of the statue from the start, the desire to make the monument a reality remained undiminished. Lydia Ely Hewitt, a Milwaukee artist who had a long-held interest in Civil War Veterans affairs, led the project for a decade attempting to find ways to raise the funds for a bronze monument that was estimated to cost $30,000 (an astounding $900,000 in today’s dollars).

John Severino Conway, an American-born sculptor, who was traveling back and forth between Milwaukee, Wisconsin and Rome, Italy, was commissioned to design the statue by Milwaukee banking and railroad magnate, Alexander Mitchell in 1885. Conway envisioned a life-sized grouping of four soldiers, one who had fallen, while three carried on dramatically with guns, swords and flag at hand. It was a metaphor for the nation, the United States had to continue on victoriously in memory of the fallen. This creation, The Victorious Charge, would become his best known work and an icon in Milwaukee.

With the design approved by Mitchell and the funds committed, the project proceeded until Mitchell’s death in 1887. A few years passed, the project languished (as did the anticipated funding) until Mitchell’s only son stated publicly that he would carry out his father’s wish to complete the statue. That was until the Panic of 1893 and the depletion of the Mitchell fortune. At this point, the Mitchell family regretfully excused themselves from the project.

All was not lost—Lydia Ely Hewitt, knowing the memorial’s importance, was undaunted. As all necessary funds could not be raised privately, she began a campaign in 1895 to raise the funds publicly. With only two-thirds of the money raised, the campaign stalled. Needing to find a way raise the amount of the funds required, she developed a remarkably simple, albeit labor-intensive, concept that would require significant collaboration. Hewitt sent standard slips of “hand-made engraved paper, watermarked ‘Soldier’s Monument, Milwaukee’” to famous persons throughout the country, soliciting their autograph. Her goal was to gather and sell the collection of signatures in order to cover the final costs of the monument.

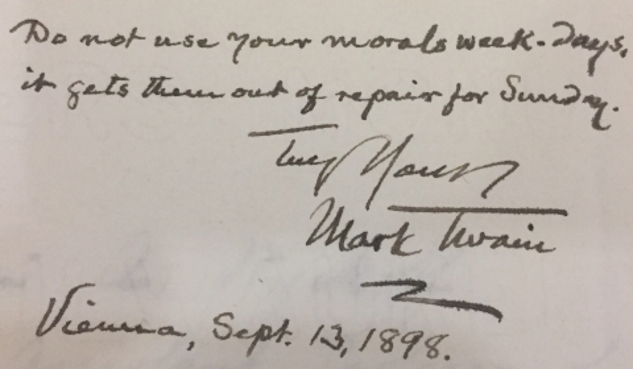

In many ways, her project captured the luminaries of the Gilded Age. Politicians, dignitaries, writers, artists, composers—even astronomers and librarians—were on Hewitt’s list of notables. The response was overwhelming. In the end, Hewitt gathered an astonishing 2,283 autographs over the course of two years. Within the collection are the signatures of two presidents and their entire cabinets, as well as the governor of every state. The book is not just filled with signatures, however. It includes messages of encouragement, drawings, and composers even penned a few bars of music on their slips. The collection reflects the imaginations and creativity of an age. Mark Twain sent a particularly wry message with his autograph, “Do not use your morals week-days; it gets them out of repair for Sunday.”

Autograph slip from Mark Twain

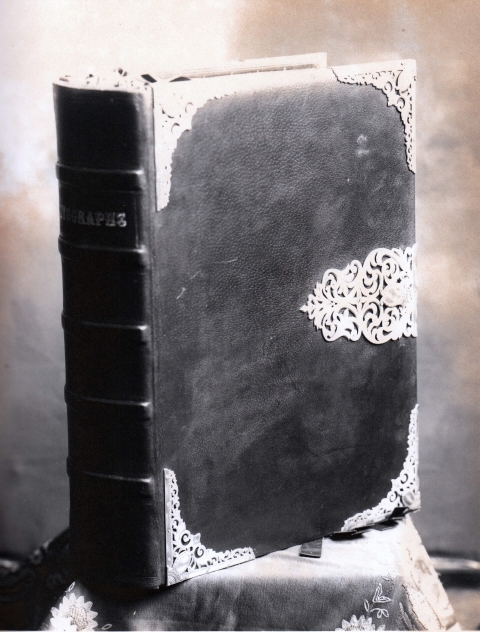

The autograph slips were organized and bound into a magnificent book of leather with silver mounts. Its scale was likely not fully realized when it went to the bindery. However, when it was completed, the book measured ten inches thick with a cover two feet by two feet, and weighed approximately 50 pounds!

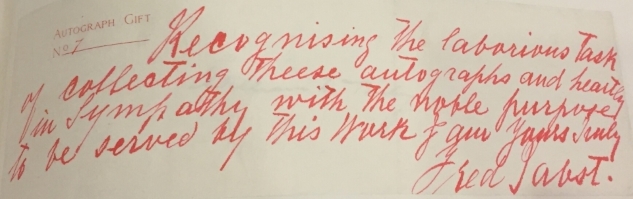

The massive tome was successful insofar as it documented an age, but to be truly successful it needed to raise enough money to finish the project — $8,000. Lydia Ely Hewitt wrote to Milwaukee’s prominent citizens, hoping that someone in the community would pay the large sum and perhaps keep the book of autographs in the community. On May 22, 1898 it was announced that Captain Pabst had come to the rescue and purchased the book for the asking price. For a decade, Captain Pabst had been seen as a champion of Civil War Veterans and his pivotal role in completing The Victorious Charge was yet another example of his support.

By early June, the statue, which had been cast in bronze in Rome, Italy, traveled across the Atlantic Ocean safely and was unveiled to the public on June 28, 1898 near the then newly completed Milwaukee Public Library on Grand Avenue, now West Wisconsin Avenue.

But what of the book of autographs that allowed the project to be completed? It remained in Captain Pabst’s possession until his death in 1904 when it was inherited by his eldest son, Gustave. Almost a decade after the Captain’s passing, Gustave wrote to the Board of Trustees of the Milwaukee Public Library and stated that he wished for the book to be accepted into their permanent collection, where he hoped it “may prove valuable and interesting to the many patrons of the Library.” For over one hundred years, the illustrious book that allowed one of Milwaukee’s best-known and highly-regarded pieces of public art to come to fruition, is still beautifully maintained at the Milwaukee Public Library.

Autograph slip from Captain Frederick Pabst

Both The Victorious Charge and the autograph book remain on West Wisconsin Avenue, a short distance from another one of Captain Pabst’s great legacies, the Pabst Mansion. The next time you are visiting us, we hope you will also appreciate our city’s public monuments and institutions shaped by the Captain himself!

Thanks to our friends at the Milwaukee Public Library for their support of this research, especially the Art, Music, and Recreation Department.